Posts

Bridge Management Systems: Safer Bridges with a Longer Lifespan at a Reduced Cost

/in Insights-Local Government, Insights-Municipal, Insights-Transportation /by Judy LincolnReduce the Cost of MS4 Compliance and Pollutant Reduction Plans Through Cooperation

/in Insights-Local Government, Insights-Municipal, Insights-Water Resources, Uncategorized /by Judy Lincoln

Stormwater management has become a major priority for environmental agencies over the past decade, and communities are struggling to meet the increasing requirements to reduce stormwater pollutants and runoff volume. The cost is simply too high for many municipalities to bear alone, but it becomes much more manageable if municipalities can share the burden with their neighbors.

Take the Pollutant Reduction Plan requirement of the MS4 application as an example. If a municipality submits a Pollutant Reduction Plan on its own, it is limited to constructing BMPs within its own borders or the drainage way of its impaired streams, but DEP will generally accept the construction of BMPs anywhere within the watershed for an MS4 permit that is submitted by a regional cooperative. This means cooperating municipalities can install BMPs that yield the greatest pollutant load reduction for the lowest cost.

Usually the largest expense associated with BMP construction is the cost of acquiring land on which to build the BMP. An individual municipality may not have much land on which to build, particularly if it is an urban municipality in which most of the available land has already been developed. As a result, the municipality may be forced to implement a large number of BMPs that each provide only marginal individual benefit in order to meet the pollutant reduction goal. If a municipality submits a regional plan with other communities in the same watershed, it will have access to a much greater land area on which to build BMPs and a reduced need for right-of-way acquisition and easements. This allows the participating municipalities to build the most effective water quality measures in the places with the greatest need.

Any improvements in upstream water quality will lead to improvements in downstream water quality, so a municipality can still see improvements in its water quality using a watershed-based approach even if a particular BMP is not located within that municipality’s borders.

When BMPs are constructed on a watershed-wide basis, the construction cost is typically lower due to economies of scale, and the water quality results are better.

Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) is working with the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority on a regional stormwater collaboration that includes 32 municipalities in Luzerne County. These municipalities intend to meet 70% of their sediment reduction goal with a single BMP: conversion of existing flood control levees into a constructed wetland with a sediment forebay and a meandering stream channel.

Regional cooperation can save municipalities money in other ways besides BMP construction. For example, the cost of preparing the Pollutant Reduction Plan itself will be much lower as a result of cooperation due to economies of scale.

Hiring a consultant to assist with pollutant reduction planning can cost thousands of dollars. If that cost is shared with 10 other municipalities, each individual municipality only has to pay a small portion.

It’s like sharing your first apartment with two roommates when you were in your 20s. The fixed cost of rent and utilities is the same whether one person lives there or three, but each person pays less if they can split that cost three ways (instead of renting their own individual apartments).

Stormwater management involves many fixed costs like the cost of owning equipment to clean out inlets or conduct outfall inspections.

Spreading those costs across a greater number of users means each user pays a smaller price for service.

Another way cooperation can reduce the cost of stormwater management is by giving municipalities increased purchasing power. Generally, you can negotiate lower unit costs for items when you buy them in larger quantities. For example, cooperating municipalities could replace or slip line several miles of pipe for a lower cost if the work was completed as part of a larger, regional project. These savings apply to the bidding of services, too. The municipalities working with the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority saved hundreds of thousands of dollars on base mapping (i.e. orthophotography, impervious area, etc.) by participating with WVSA under a single project (rather than having each municipality bid its own contract).

Municipalities have greater purchasing power when they cooperate on stormwater management solutions. For example, cooperating municipalities could slip line several miles of pipe for a lower cost if the work was completed as part of a larger, regional project.

A regional cooperative also has more borrowing power than a single municipality, and funding agencies are more likely to award a grant or loan to a regional project than one submitted by a single municipality. Funding agencies prefer regional projects because they believe regional cooperation streamlines costs, and politicians tend to support projects that benefit as large a constituent base as possible. A regional initiative should be tied together by legal agreements that assure the funding agency all funding will be properly administered. (These legal agreements are also required to meet DEP requirements for submission of a regional pollution reduction plan.)

This post is an excerpt from a longer article in the July-August-September issue of Keystone Water Quality Manager magazine. The article is focused on the cost savings communities enjoy by cooperating with regional partners on their stormwater management programs. Read the magazine for advice on finding partners for your stormwater management program or contact us to request a copy.

Erin G. Letavic, P.E., is the regional manager of civil engineering services in HRG’s Harrisburg office. She guides municipalities and cooperative groups throughout Pennsylvania through the management of their MS4 permits, provides grant application development and administration services, and provides retained engineering services to local government.

Adrienne Vicari, P.E. is the financial services practice area leader at Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG). She provides strategic financial planning and grant administration services to numerous municipal and municipal authority clients. She also serves as project manager for several projects involving the creation of stormwater authorities or the addition of stormwater to the charter of existing authorities throughout Pennsylvania.

Regional Stormwater Plan to Save Taxpayers Money in Luzerne County

/in Insights-Environmental, Insights-Local Government, Insights-Municipal, Insights-Water Resources, Uncategorized /by Judy LincolnThis article is an excerpt from the December 2017 issue of The Authority, a magazine produced by the Pennsylvania Municipal Authorities Association (PMAA). It is the second in a series of 3 articles about an innovative approach to stormwater management and MS4 compliance being pioneered by 31 municipalities and the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority. You can read the first article here: How Municipalities in the Wyoming Valley Are Cutting Stormwater Costs by Up to 90% )

Thirty-one municipalities in Luzerne County are piloting a regional approach to MS4 compliance that may revolutionize the way Pennsylvania responds to the growing challenges posed by stormwater.

They have signed cooperative agreements with the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority, which will serve as MS4 permit coordinator for the entire region. In our previous post, we discussed the many ways a regional partnership can lower the cost of stormwater management for municipalities.

In this post, we’ll discuss how:

Cooperation benefits the taxpayer.

If regional cooperation lowers the cost of stormwater management, it stands to reason those cost savings will be passed on to the taxpayer. But, make no mistake, replacing aging infrastructure and constructing Best Management Practices will cost money, and that money will have to come from somewhere.

With municipal budgets already stretched to the limit, communities may have to consider new revenue sources. That could mean a tax increase or a stormwater fee.

Stormwater fees are generally a better deal for the average constituent. This is because a fee structure ensures everyone pays their fair share.

If taxes were raised to cover the cost of stormwater management, many property owners with large amounts of impervious area would be exempt: hospitals, schools, and other non-profit institutions. However, these institutions can sometimes be the biggest contributors to a community’s stormwater issues because stormwater runoff occurs when the water runs along impervious surfaces and cannot infiltrate the ground.

If stormwater management is paid for through a property tax increase, these non-profit organizations won’t pay for the services they’re using, but someone will have to, and that burden will fall on homeowners and small businesses.

Studies show time and again that the average homeowner would pay less for stormwater management if he or she were charged a stormwater fee than if the municipality raised property taxes.

The regional cooperation being pioneered by the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority is an especially good deal for local taxpayers: Our analysis showed that the average residential property owner will save 70 – 93% by paying a regional stormwater fee instead of paying an increased property tax.

The Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority’s estimated stormwater fee is between $3.00 and $4.50 per month. This is lower than the other stormwater fees currently being paid throughout Pennsylvania, which average between $6.50 and $8.50 per month.

By using a regional approach, WVSA is able to lower costs beyond what an individual municipal authority could likely achieve. These numbers are even more impressive when you consider that the fees for most of the other municipal authorities included in the average above were calculated before taking 2018 MS4 permit requirements into account. Therefore, those communities may actually have to raise fees higher to meet the stricter requirements coming in the next permit cycle. WVSA’s estimated cost already accounts for the 2018 permit requirements.

Municipal leaders are stewards of the public’s money, but they are also stewards of the environment. In our next post, we’ll discuss how regional cooperation on stormwater management can more effectively keep our rivers and streams clean for drinking, agriculture, and recreation.

Jim Tomaine has more than 30 years of engineering experience. He holds a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering from The Pennsylvania State University and a master’s degree in business administration from Wilkes University. He is the executive director of the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority and has been at WVSA for twenty seven years. Prior to the WVSA, Mr. Tomaine worked in the private sector as a design engineer. He currently holds his A-1 Wastewater Treatment Plant Operators Certification in Pennsylvania and is also a registered professional engineer.

Adrienne Vicari is the financial services practice area leader at Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG). In this role, she has helped the firm provide strategic financial planning and grant administration services to numerous municipal and municipal authority clients. She is also serving as project manager for several projects involving the creation of stormwater authorities or the addition of stormwater to the charter of existing authorities throughout Pennsylvania.

How Dauphin County Has Turned a Small Surplus Into Major Infrastructure Improvements

/in Insights-Financial, Insights-Local Government, Insights-Planning, Insights-Transportation /by Judy LincolnThis article about the Dauphin County Infrastructure Bank is excerpted from the February 2018 issue of Pennsylvania County News magazine. It is provided courtesy of the County Commissioners Association of Pennsylvania (CCAP) and is reprinted here with their permission. This is in no way an endorsement by CCAP of the products or services offered by HRG.

What would you do with an extra $350,000 per year in your county Liquid Fuels budget?

It sounds like a nice problem to have, doesn’t it?

That’s exactly the challenge Dauphin County faced six years ago as its aggressive bridge management program reached a very important milestone: The last load-posted, structurally deficient bridge in the county’s inventory was fully programmed to be replaced.

This video tells the story of the last structurally deficient bridge in Dauphin County. Once the county funded the replacement of this bridge, it had a surplus of Liquid Fuels money in its budget. They decided to use this surplus as seed money for an infrastructure bank that has funded more than a dozen roadway, traffic and bridge improvements throughout the county in just a few years. (Learn more about the county’s last structurally deficient bridge in this profile.)

For almost 30 years, the county had patiently and strategically planned the rehabilitation or replacement of 51 bridges. Close to 1/3 of its county-wide inventory had been structurally deficient at the time they embarked on this effort in 1984.

Now that hard work and determination was about to pay off. The county could drastically reduce its spending on bridge capital improvements by shifting from a replacement phase to a maintenance phase.

The county’s engineer, Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG), analyzed what investments would be necessary to proactively maintain the bridges and determined that the county would have an annual surplus of approximately $350,000 in Liquid Fuels funding beyond what was needed for maintenance expenses.

County commissioner Jeff Haste wanted to make sure the money was used wisely: “The county’s bridge management program had delivered tremendous value to our residents, drastically improving the safety and efficiency of our transportation system for drivers. We wanted to use this money to deliver even more value.”

County Commissioners Haste, Pries and Hartwick wanted to maximize the benefit of these surplus dollars for county residents. The infrastructure bank approach has allowed them to fund more than $11 million in improvements with an initial investment of $1 million.

Haste and his fellow commissioners, Mike Pries and George P. Hartwick, III, were thinking big, but regulatory requirements threatened to make the impact of this money small.

“Because of the forced distribution procedure associated with Liquid Fuels funding,” Haste explained, “the county had to come up with a use for this money or disburse it evenly to all 40 of our member municipalities.”

On average, each municipality would’ve received less than $10,000, which is too small a sum to do anything more significant that buy a little extra road salt for the winter.

Yet, even if the county used the entire $350,000 surplus itself, they wouldn’t be able to cover the cost of even one small capital improvement like a single-span bridge replacement (which typically costs between $500,000 to $1 million).

Haste, Pries and Hartwick wanted to have a larger impact, so they asked county staff to collaborate on a solution with the engineer who’d designed the successful bridge management program in the first place.

Together, they came up with an innovative program in which the county would use this annual Liquid Fuels surplus to dramatically reduce the cost of infrastructure improvements for local municipalities.

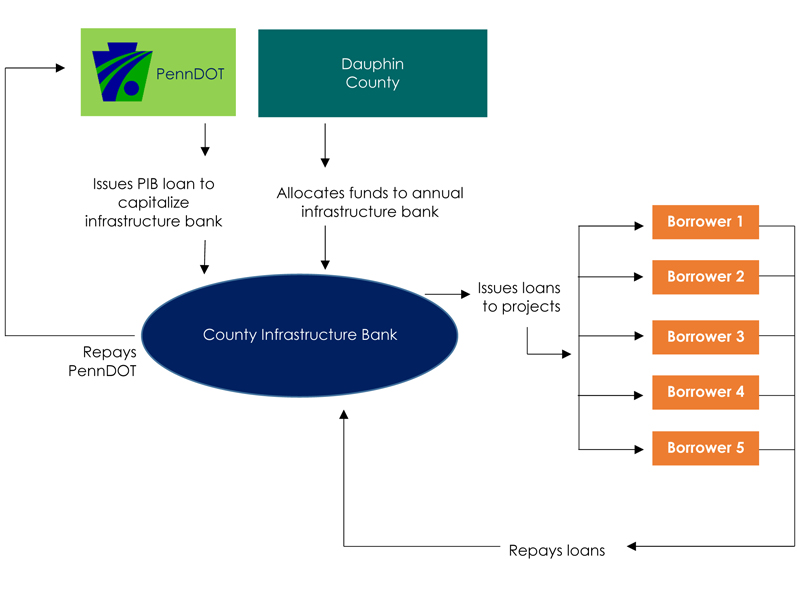

How the Dauphin County Infrastructure Bank Works

The Dauphin County Infrastructure Bank offers loans to municipalities (or private sector companies) to design and construct local roadway, bridge and traffic improvements – at unbeatably low interest rates. Municipalities can borrow money for as little as 0.5% interest. (Private sector borrowers pay a 1% interest rate.)

As an added bonus, Dauphin County provides loan recipients with optional engineering design support. This is very beneficial to smaller municipalities who have never completed a large capital improvement project before and may not know how to navigate the complicated state and federal requirements these projects must meet. An experienced consultant can save these municipalities from costly and time-consuming mistakes and re-work.

But, if $350,000 wasn’t enough money for the county to complete one major capital improvement project on its own, how can it use that money to fund multiple projects by its municipalities?

The power of partnerships.

Dauphin County multiplies the value of its $350,000 investment by combining it with additional funding from Pennsylvania’s state infrastructure bank.

Essentially, the county uses its Liquid Fuels surplus to make it more affordable for municipalities and private sector organizations to borrow money from the state by paying a portion of their interest. Interest on Pennsylvania Infrastructure Bank loans can vary, but it is currently 2.125% at the time this article is being written.

A municipality could borrow funds directly from the Pennsylvania Infrastructure Bank at an interest rate of just over 2%, or it could borrow from Dauphin County, and the county would pay approximately 75% of the interest expenses.

The following diagram shows exactly how the Dauphin County Infrastructure Bank funds its projects:

It is a self-renewing process. As municipalities or private sector organizations repay their loan to the county infrastructure bank, the county repays PennDOT. Once the debt is satisfied, the county has the ability to issue new loans to other municipalities or private sector companies.

For some municipalities, the cost savings provided by an infrastructure bank loan can be the difference between being able to move forward with a project at all or having to postpone it a few more years.

In the first three years of the infrastructure bank program, Dauphin County multiplied close to $1 million in Liquid Fuels funding into $11 million worth of improvements to the local transportation system: 7 bridges, one traffic signal, one streetscape, and one intersection improvement.

This streetscape project in Middletown Borough is one of the projects that has been funded by the Dauphin County Infrastructure Bank. You can read more about the award-winning project and its potential economic benefit for the community in this article from The Authority.

“This is the kind of dramatic impact we were hoping to have,” says Pries, who oversees Dauphin County’s Community and Economic Development Department.

“The success of our bridge program and the creation of the Dauphin County Infrastructure Bank has allowed us to help residents without the need to raise property taxes. Unlike many other parts of the country, our residents don’t have to worry about crumbling bridges and road networks.”

Read more about the Dauphin County Infrastructure Bank, the benefits of implementing an infrastructure bank in your county, and other counties that are considering a program of their own in the February 2018 issue of Pennsylvania County News.

Brian Emberg, P.E., is senior vice president and chief technical officer of Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG). He helped design Dauphin County’s bridge management system and worked with the county to develop the Dauphin County Infrastructure Bank. He has more than 30 years of experience designing roadways and bridges and is particularly skilled in creating unique funding solutions to help local governments accomplish their infrastructure goals with limited revenue. You can contact Brian by phone at (717) 564-1121 or by email at bemberg@hrg-inc.com

Learn more about our work with the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority in this 3-part series published in The Authority, a magazine published by the Pennsylvania Municipal Authorities Association.

Learn more about our work with the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority in this 3-part series published in The Authority, a magazine published by the Pennsylvania Municipal Authorities Association.