Form-Based Zoning Can Bring Municipalities and Developers Together on the Walkable Communities Buyers Want

Photo by North Charleston. Published here under a Creative Commons license.

The National Association of Realtors (NAR) recently released the results of a nationwide poll showing millennials increasingly prefer walkable communities over the spread-out developments in many present-day suburbs. Other studies have confirmed similar preferences for walkable neighborhoods and mixed-use development; however, traditional zoning approaches, which emphasize low-density development and a separation of land uses, makes it difficult for residential developers to obtain approval for these communities. This article explores the rise in popularity of the walkable community and discusses how residential developers and municipal planners can use form-based zoning to create a community that meets the needs of everyone.

The Case for Walkable Communities

In 2013, NAR’s Community Preference Survey found that 60% of respondents preferred a neighborhood that mixes housing with stores and businesses within walking distance, and 55% would give up a home with a bigger yard in order to get one within walking distance of schools, stores and restaurants.

Additionally, a study by Gary Pivo at the University of Arizona’s Urban Planning Program and Jeffrey Fisher at Indiana University’s Kelly School of Business found that – other factors being equal – enhanced walkability increased the value of both residential and commercial properties. Using data from the National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries and Walk Score, they compared more than 4,000 office, apartment, retail and industrial properties and determined that a 10% increase in walkability increased property value by up to 9% for all but the industrial properties. (There was no discernible impact on industrial properties with a higher walkability score.)

This is in line with other studies of traditional neighborhood developments (TND) published in Real Estate Economics and the Journal of Urban Economics, which found that buyers were willing to pay between 12-15% more for pedestrian-friendly homes in the studied neighborhoods, compared to similar homes in neighboring low-density communities.

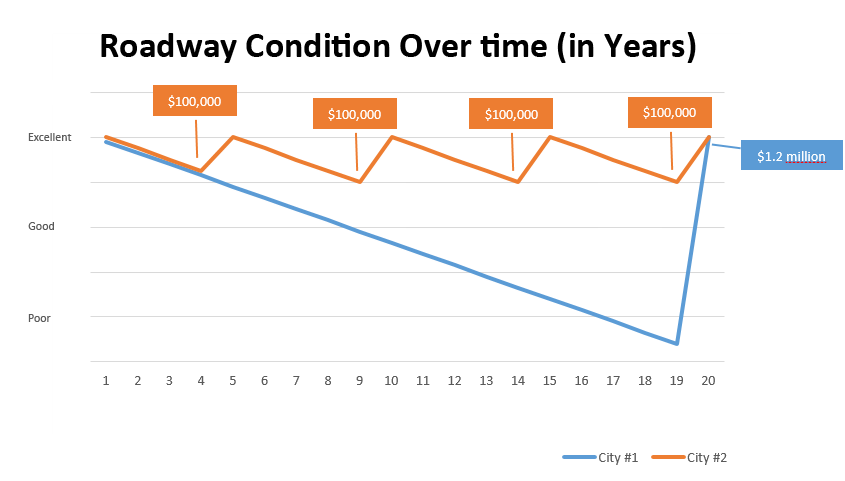

Increased property values benefit the developer selling the home, but they also benefit the local municipality as they increase property tax revenues. In addition, high density, walkable communities reduce the amount of infrastructure (such as roadways, traffic signals, water and sewer line extensions) needed to connect spread-out developments, which can save the municipality money that would’ve been needed to maintain that infrastructure.

The most important reason for municipalities to consider making their zoning friendlier to walkable communities, however, might be their desire to stay competitive as a place people want to live.

Millennials represent a demographic of 80 million people, and they are the generation that will be buying homes and putting down roots in the years to come. Michael Myers, a managing director at The Rockefeller Foundation, is quoted in an article on The Atlantic’s CityLab website, saying, “As we move from a car-centric model of mobility to a nation that embraces more sustainable transportation options, millennials are leading the way…Cities that don’t invest in [these options] stand to lose out in the long run.”

Bridging the Municipal-Developer Gap with Form-Based Zoning

If municipalities and developers agree that walkable communities can be beneficial, why aren’t more of them being built?

Over the past few years, these communities have become more and more popular with both developers and municipalities, but acceptance still is not widespread. Traditional zoning ordinances could be one of the reasons why.

Traditional zoning ordinances separate land uses into distinct zones: Commercial is separate from residential. Single family homes are separate from apartments and townhomes, etc. This prevents the construction of developments that combine commercial and residential uses of different types in one space like modern walkable communities do. In addition, traditional zoning has emphasized a low-density approach because communities associate higher density with a loss of open space and community character and fear higher density developments will drain community resources. However, developers require a higher density approach in order to make the many amenities (such as recreational facilities and civic and commercial spaces) affordable in a typical walkable community plan.

But form-based zoning could be the bridge that closes the gap between a community’s concerns and a developer’s needs.

Rather than fixating on density values and strict land use definitions, municipalities using a form-based zoning approach create a vision for the type of community they’d like to have and set standards to realize that vision. If they want a community that encourages walking and social interaction in public spaces, they can set standards that will promote these activities. For example, Public Space standards can specify the types of pedestrian amenities, greenspaces and recreation requirements that make a place feel safe, comfortable and walkable. They can also set the size of a standard block and govern how roadways and pedestrian amenities interconnect. (Keeping the size of blocks small will make them more manageable for walkers, and interconnecting streets will provide shorter routes and more evenly distribute car traffic throughout the roadway network. This will, in turn, have the added benefit of reducing congestion that comes from concentrating cars on just a few heavily travelled corridors, as is common in many traditionally zoned communities today.)

By using a form-based approach, municipalities can focus more on the form and feel of a community, instead of limiting development to strictly separated zones with a one-size-fits-all regulation of lot sizes.

In turn, residents enjoy the quality of life they seek, and municipalities can continue to attract growth, maintain a healthy tax base, and reduce the expenses associated with sprawling infrastructure. Meanwhile developers are able to meet a market demand profitably without navigating an unnecessarily lengthy entitlements process.

This type of approach allows communities to remain relevant and competitive in the decades to come as millennials age, take their resources and preferences to market, have kids and nurture the next generation. Municipalities and developers that dismiss these trends as merely a fad may be taking a big risk. Is it worth it? We will know in 20 years.

HRG excels at bringing developers and municipalities together to meet the needs of a community in a way that benefits all parties. To discuss how walkable communities could benefit you, please contact us.

Matthew Cichy, P.E. is a water and wastewater senior project manager responsible for a variety of engineering tasks, including water and wastewater facilities planning, the design of water distribution systems, wastewater collection and conveyance systems, pumping stations, and water and wastewater treatment plants as well as construction administration, field inspections, financial consulting, and project management.

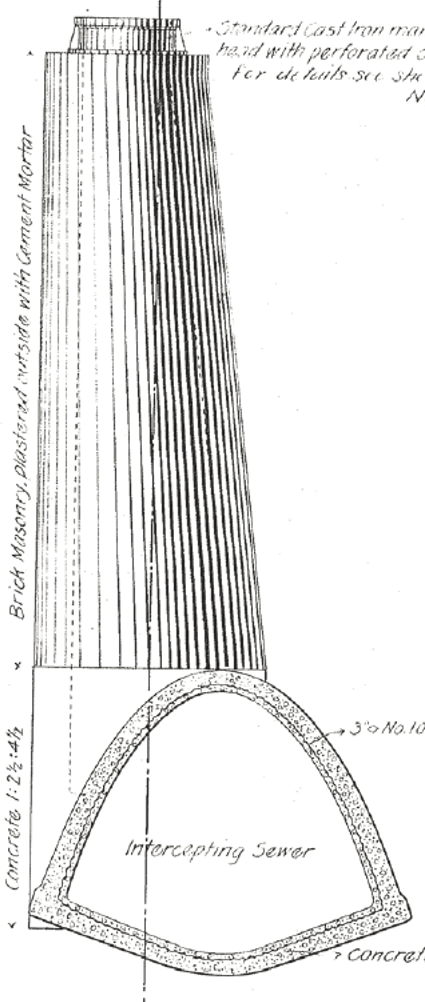

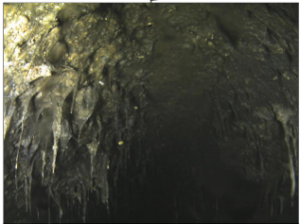

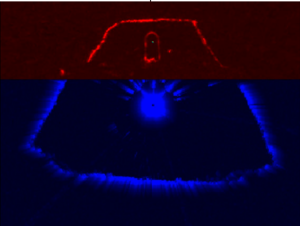

Matthew Cichy, P.E. is a water and wastewater senior project manager responsible for a variety of engineering tasks, including water and wastewater facilities planning, the design of water distribution systems, wastewater collection and conveyance systems, pumping stations, and water and wastewater treatment plants as well as construction administration, field inspections, financial consulting, and project management. Bruce Hulshizer, P.E. is also a project manager in HRG’s water and wastewater service group. He has two decades of experience in civil engineering and is an active member of the Pennsylvania Water Environment Association, where he serves as their co-chair of the Collection System Committee for 2015.

Bruce Hulshizer, P.E. is also a project manager in HRG’s water and wastewater service group. He has two decades of experience in civil engineering and is an active member of the Pennsylvania Water Environment Association, where he serves as their co-chair of the Collection System Committee for 2015.

Adrienne Vicari, P.E., is the financial services practice area leader at HRG. In this role, she has helped the firm provide strategic financial planning and grant administration services to numerous municipal and municipal authority clients. She is also serving as project manager for several projects involving the creation of stormwater authorities or the addition of stormwater to the charter of existing authorities throughout Pennsylvania.

Adrienne Vicari, P.E., is the financial services practice area leader at HRG. In this role, she has helped the firm provide strategic financial planning and grant administration services to numerous municipal and municipal authority clients. She is also serving as project manager for several projects involving the creation of stormwater authorities or the addition of stormwater to the charter of existing authorities throughout Pennsylvania.