Posts

Ginny Loaney Promoted to Land Development Group Manager

/in Company News, News – Landscape Architecture, News-Land Development /by Judy Lincoln Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) is pleased to announce that Virginia Loaney has been promoted to Land Development Group Manager in our Pittsburgh office.

Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) is pleased to announce that Virginia Loaney has been promoted to Land Development Group Manager in our Pittsburgh office.

Loaney joined HRG in 2016 as a landscape architect and has 15 years of experience in the healthcare, education, recreation, government, commercial and residential markets.

In her new role as group manager, Loaney will take on additional supervisory and business development responsibilities, striving to expand the presence of HRG in the land development market and build lasting relationships with clients and teaming partners.

HRG Assistant Vice President Jim Feath says, “Ginny skillfully balances rigorous engineering standards with creativity and collaboration to achieve her client’s aspirations. She brings diverse stakeholders together to achieve the most complex goals, thanks to her outgoing, conscientious personality and brilliant, purposeful approach to planning and design.”

ABOUT HRG

Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) is a nationally ranked design firm providing civil engineering, surveying, and environmental services. The firm was founded in Harrisburg in 1962 and has grown to employ more than 200 people in West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. For more information, please visit the website at www.hrg-inc.com.

5 Economic Benefits of Parks and Recreational Facilities

/in Insights-Landscape Architecture, Insights-Municipal, Insights-Planning, Insights-Recreation, Uncategorized /by Judy LincolnStaub, Feath Discuss Demographic Shifts and Impact on Local Government

/in Company News, News-Municipal /by Judy Lincoln Our assistant vice presidents Tim Staub and Jim Feath are both featured in the March 2019 issue of Pennsylvania Township News magazine cover story, offering some insight on how municipalities can adjust policy and prepare for the needs of an aging population.

Our assistant vice presidents Tim Staub and Jim Feath are both featured in the March 2019 issue of Pennsylvania Township News magazine cover story, offering some insight on how municipalities can adjust policy and prepare for the needs of an aging population.

According to the article, 235 township residents in Pennsylvania turn 65 every day, and older adults are projected to outnumber adults for the first time time in U.S. history by 2035.

“Just how well-positioned is your community to allow them to age in place?” Tim asks.

He offers a number of ideas for making sure your township can retain residents as they age:

- promoting walkability with sidewalks and connections between neighborhoods and amenities

- incorporating universal design elements into construction standards that help residents stay in their home

- permitting multi-generational living arrangements such as shared housing and accessory dwelling units

The key, he says, is to make your zoning and construction codes flexible enough to accommodate the changing needs of your community.

Jim Feath discusses how to provide recreational facilities that meet seniors’ needs, but he also recommends analyzing local population trends before making any significant changes. Some municipalities are seeing an influx of young families. Township officials will want to provide facilities that meet the need of their individual community, not just chase trends. (HRG can help and often provides this service as part of a larger comprehensive plan or comprehensive recreation plan. Two of our clients — Cranberry Township and Dover Township — are also featured in the article, sharing the ways they proactively plan for their communities’ evolving needs.)

How to Incorporate Green Infrastructure into Parks in order to Save Money Meeting Regulatory Requirements

/in Insights-Environmental, Insights-Landscape Architecture, Insights-Municipal, Insights-Recreation, Insights-Water Resources /by Judy LincolnThis article is the third in a series on incorporating green infrastructure into parks and recreational space in order to more cost-effectively meet environmental regulatory requirements. (Part 1 explained why parks are an ideal location for green infrastructure projects to meet regulatory requirements, and Part 2 explained the benefits of incorporating green infrastructure into parks.)

In this article, we provide advice on how communities can identify areas in their park and recreational spaces that are good candidates for green infrastructure and how to work with other groups to get these projects implemented. This article is an excerpt from an article we published in the April 2018 issue of Borough News magazine entitled “Parks Provide the Ideal Location for Meeting Environmental Regulatory Requirements.”

How can municipalities incorporate green infrastructure into their park facilities?

Start by taking an inventory of your facilities and look for places where green infrastructure could be used.

Pay close attention to your hard surface areas. These are the areas that generate the most runoff, so look for ways to reduce the amount of hard surface area or lessen its impact by directing runoff to pervious areas.

Look at your parking lots: How does stormwater flow across the lot? Are there landscaped areas or medians where you could incorporate bioretention facilities? Are there places where you could plant additional trees? Perhaps you could use permeable pavement in the parking stalls.

Watch this video to see a demonstration of how quickly permeable pavement in these municipal parking stalls absorbs a few buckets of water compared to the non-permeable pavement outside the parking stalls.

Do you have paved trails and walkways in your park system? Consider permeable pavement or a tree canopy that runs alongside the path. Because of their linear nature, bioswales can be planted alongside trails or paved paths, too. The following video shows how a system of bioswales along the bike trail in Indianapolis absorbs water during a rain event.

The Magnificent Bioswales & Stormwater Treatment Along the Indy Cultural Trail from STREETFILMS on Vimeo.

Could your athletic fields be used for a dry extended detention basin?

Do you have open space within existing drainage areas that could be used for constructed wetlands?

Do you have a community center? This would be a great location for a demonstration rain garden, rainwater harvesting system, or planter boxes. It could even be a candidate for a green roof.

Middletown Borough reduced the volume of stormwater entering their stormwater system by converting the traditional garden located between their municipal building and parking lot to a rain garden. By redirecting the building downspout to the rain garden, the stormwater that previously flowed across the parking lot is now infiltrated on site.

Check out this article in the Middletown Press and Journal about Middletown’s rain garden.

Successfully integrating green infrastructure into your park facilities is a team effort. Municipal administration, public works staff, planners, and the parks and recreation department should all work together to find cost-effective solutions that maximize benefits for the community.

But the teamwork shouldn’t end inside the government offices. Schools, conservation groups, gardening clubs, and other community groups may also want to lend a hand. Bringing them on board marshals additional resources for the cause and helps to build public support for the efforts.

Your municipal engineer can provide valuable guidance on design, regulatory requirements and even potential funding sources.

Municipal staff must be creative stewards of both the environment and the taxpayers’ money. Incorporating green infrastructure and streambank restoration projects into park and recreational facilities helps them do both. By using land the municipality already owns, communities can greatly reduce the cost of construction projects needed to comply with environmental regulation like the MS4 program. The native plantings used in rain gardens and bioswales typically need less maintenance and chemicals than turf grass, and rainwater collected in barrels can be used for irrigation or toilet flushing in order to lower water consumption costs.

At the same time, these projects prevent pollutants in stormwater runoff from reaching our lakes and streams, preserving them for recreational uses like fishing and swimming. They also help to prevent flooding, which ensures the parks department will be able to keep athletic fields and parks open for scheduled activities after a storm.

In these ways, green infrastructure can enhance the recreational experience for the user. It can also enhance the aesthetic appeal: Rain gardens and native vegetation can provide a habitat for wildlife and butterflies for safe public viewing and can serve as a quiet retreat for reflection.

Signage turns these features into an educational experience and helps to meet the educational outreach requirements of a community’s MS4 permit.

Working together as a team, municipal officials, planners, park professionals, and local community groups can protect our resources while providing exceptional recreational experiences for all.

Ben Gilberti, P.E., manages civil engineering services provided by Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) throughout Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. He assists with the design of municipal infrastructure like sidewalks, stormwater systems, and sewer facilities.

Ben Gilberti, P.E., manages civil engineering services provided by Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) throughout Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. He assists with the design of municipal infrastructure like sidewalks, stormwater systems, and sewer facilities.

James Feath, R.L.A., is a senior landscape architect at HRG. He has 20 years of experience in the planning and design of public spaces, including parks, trails, and recreational facilities.

James Feath, R.L.A., is a senior landscape architect at HRG. He has 20 years of experience in the planning and design of public spaces, including parks, trails, and recreational facilities.

Benefits of Installing Green Infrastructure in Parks for MS4 Compliance

/in Insights-Environmental, Insights-Landscape Architecture, Insights-Local Government, Insights-Municipal, Insights-Recreation, Insights-Water Resources /by Judy LincolnLast week, we shared how parks and recreational space can be the ideal location for green infrastructure and streambank stabilization projects that help you meet your MS4 compliance and pollutant reduction plan goals. This week we discuss the benefits of this approach in another excerpt from an article we published in the April 2018 issue of Borough News magazine.

As we stated last week, the latest round of MS4 permitting requires many municipalities to implement a pollutant reduction plan that reduces the level of pollutants in their stormwater by as much as 10%. This will likely involve the construction of Best Management Practices (BMPs) like rain gardens or streambank stabilization projects, and the most expensive part of BMP construction is often acquiring the land on which to build. This is why parks and recreational space can be an ideal location for BMPs because it’s land you already own; there are no land acquisition costs.

Middletown Borough is proposing to meet the majority of its MS4 pollutant reduction plan goal with the installation of a bioretention basin along the east side of Hoffer Park. This basin will be created by excavating an existing corrugated metal stormwater pipe and backfilling the trench with layers of bioretention bed components like engineered media, topsoil and mulch. Water-tolerant native plantings will then be planted there.

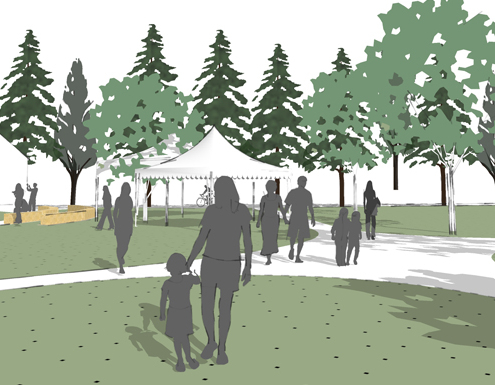

Wilkins Township in Allegheny County is also proposing improvements to one of its municipal parks as part of it MS4 pollutant reduction plan. The township is upgrading Lions Park to include ADA accessible routes, a paved walking trail, playground, deck hockey and pavilion. Many green infrastructure elements are being incorporated into the park design in order to manage stormwater on-site. For example, soil in all open spaces will be amended to enhance its structure and ability to promote infiltration. A rain garden will be planted along with vegetated channels and a vegetated filter strip, as well.

Green infrastructure can save money in other ways, too.

- Funding agencies often prefer projects that provide multiple benefits, so municipalities may be able to increase the opportunity for grant money by combining recreational and environmental goals into the same park improvement project. As part of the grant requirement for funding from the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Lower Swatara Township integrated water quality BMPs into the rehabilitation plan for the playground at two of their community parks. The runoff from the playground area will be conveyed into rain gardens adjacent to the new playground and will be treated on site. The walkways from the parking area to the new playground will be porous asphalt to minimize the amount of runoff. Additionally, educational signage will be installed to educate playground visitors on the environmental and water quality benefits provided by the rain gardens.

- Captured rainwater can be used for irrigation or toilet flushing, thereby reducing potable water consumption.

By SuSanA Secretariat [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

A rainwater harvesting system

But the benefits of incorporating green infrastructure into your park facilities go beyond saving money:

Green infrastructure can improve the recreation experience for park users.

- Natural vegetation can provide a habitat for wildlife and offer the opportunity for wildlife viewing.

- Vegetation can also reduce noise and provide visual barriers to set off private areas for picnics or meditation.

- Green infrastructure helps to ensure adequate flows in ponds and streams , so that park users can enjoy them.

Photo by ChattocaneeNF. Used under a Creative Commons license.

- It is generally more attractive than large swaths of concrete piping and basins.

- It improves drainage, which means park facilities are less likely to flood (and less subject to closure or cancellation of activities after a storm). North Middletown Township has proposed a bioretention basin in Village Park as part of its Chesapeake Bay pollutant reduction plan, but an added benefit of the basin is that it will help to prevent the frequent flooding of a playground within the park during heavy rain events.

Green infrastructure can reduce maintenance.

- Standing water is a breeding ground for mosquitos, so maintenance personnel must be vigilant to prevent it. Improving drainage will reduce the effort needed to eliminate standing water.

- Turf grass can be high maintenance. Rain gardens and bioswales can be populated with native vegetation that requires less watering, no chemicals, and less mowing or weeding.

- Vegetation along streambanks can slow or even absorb runoff before it reaches the stream, thereby reducing erosion. The vegetative root structures hold sediment in place to further reduce streambank erosion.

Installing green infrastructure in parks provides an opportunity to educate the public and encourage good habits.

- Signs explaining how green infrastructure works can be used to meet MS4 education requirements under Minimum Control Measure #1. Cranberry Township, Butler County, is including signage about the bioswales they’re installing in Graham Park for this very reason. Schools and community groups can visit the site and learn how stormwater is managed. Park visitors can read the signs and may even be inspired to install green infrastructure on their own property. This extends the environmental benefits even further. The Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority has pioneered an innovative regional partnership among more than 30 municipalities to cooperate on stormwater management and MS4 compliance. Their plan includes the creation of stormwater parks that will combine green infrastructure with signage to educate the public. (You can read more about WVSA’s award-winning initiative here. You can also read more about the wide-ranging services we’ve provided at Graham Park.)

Photo by Doug Kerr. Used via a Creative Commons license.

Signage turns green infrastructure in parks into an educational piece that can be used to meet MS4 MCM #1 requirements.

To sum it up: Incorporating green infrastructure into your park and recreational facilities allows you to provide a better experience for your residents while minimizing the cost of complying with environmental regulation and reducing future maintenance needs. It’s win-win-win!

In next week’s post, we’ll talk about how municipalities can incorporate green infrastructure into their parks and recreational spaces, including how to identify locations for green infrastructure and how to coordinate with other groups to get the projects built.

Ben Gilberti, P.E., manages civil engineering services provided by Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) throughout Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. He assists with the design of municipal infrastructure like sidewalks, stormwater systems, and sewer facilities.

James Feath, R.L.A., is a senior landscape architect at HRG. He has 20 years of experience in the planning and design of public spaces, including parks, trails, and recreational facilities.

Parks Provide the Ideal Location for Meeting Environmental Requirements

/in Insights-Environmental, Insights-Landscape Architecture, Insights-Local Government, Insights-Municipal, Insights-Recreation /by Judy LincolnThis post is an excerpt from an article we published in the April 2018 issue of Borough News magazine entitled “Parks Provide the Ideal Location for Meeting Environmental Regulatory Requirements.”

Parks aren’t just for fun and relaxation. They deliver significant value to the community, increasing property values, promoting health and wellness, and providing a gathering spot for people to socialize and get to know their neighbors. Did you know they can also help your municipality address environmental concerns like flooding, water pollution, and streambank erosion? This makes them an ideal location for meeting the regulatory requirements contained in the MS4 program.

The latest round of permitting added a new requirement for many municipalities to quantify the level of pollutants they are contributing to the watershed and execute a plan to reduce that level by as much as 10%. Municipalities can meet these requirements by implementing Best Management Practices (BMPs) like green infrastructure and streambank stabilization projects.

The most expensive part of these projects is often buying the land on which to build, so why not use land the municipality already owns in its parks and recreational facilities?

Green Infrastructure

The wide expanses of open space that parks contain are a natural fit for BMPs like green infrastructure.

Green infrastructure uses plants, soils and engineered materials to mimic the processes that absorb water and filter pollutants in nature.

When rain falls on developed property, it sits on the pavement or is directed into pipes and inlets.

Concentrating the water in this way contributes to erosion, and, when too much rain falls at once, those pipes can be overwhelmed. Then flooding occurs. In urban areas, the rain water often carries trash and other pollutants into the waterways, as well.

Photo by Clean Bread and Cheese Creek. Used via a Creative Commons License.

This is not the case in nature. Rain water that falls on undeveloped land is absorbed into the ground. Plants and vegetation filter chemicals and other pollutants from the water before it can reach our lakes and streams. Green infrastructure seeks to replicate this process.

Examples of green infrastructure include:

- Rain gardens

- Bioswales

- Permeable Pavement

Rain gardens are shallow basins lined with water-tolerant native plants and amended soil media that collect and absorb stormwater runoff. They are also sometimes called bioretention or bioinfiltration basins.

By BrianAsh at English Wikipedia(Uploads) (Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons.) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Bioswales are similar to rain gardens, but they are lined with plants that also filter pollutants from the runoff before it is absorbed into the ground. They are typically long and narrow and are thus well-suited for placement along streets and parking lots.

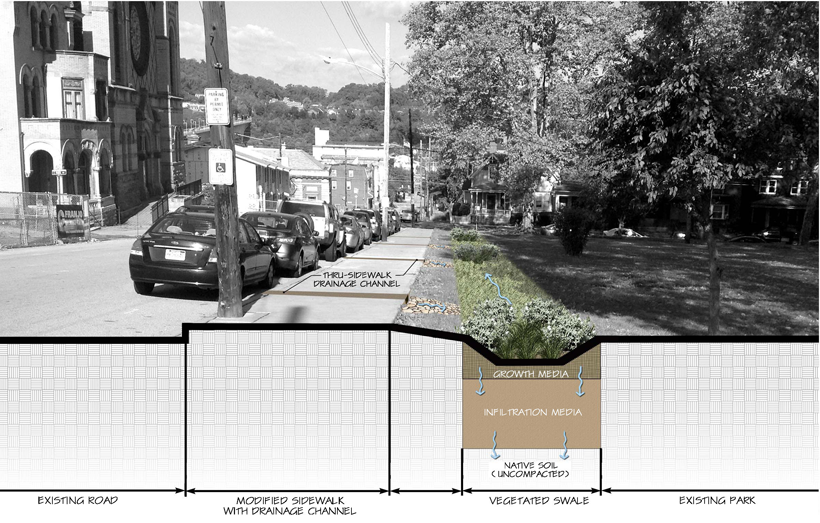

HRG helped identify green infrastructure opportunities for the Allegheny County Sanitary Authority (ALCSOSAN) that would help them address stormwater issues. This is a rendering of a bioswale in Frick Park along Amity Street in Homestead.

Permeable pavement is asphalt or concrete that is made to infiltrate runoff. Unlike conventional asphalt, permeable pavement is porous, and those pores allow water to seep into the ground. Often a layer of aggregate or stones is placed underneath the surface pavement to help filter and store the water before it is absorbed into the soil.

Volunteers demonstrate how permeable pavement in the parking lot of a shopping center absorbs the water.

Watch a video about permeable pavement HRG incorporated into the West Caracas Avenue parking lot in Derry Township. This video aired on by Fox43, a local news station in Central Pennsylvania.

HRG incorporated into the West Caracas Avenue parking lot in Derry Township. This video aired on by Fox43, a local news station in Central Pennsylvania.

Other examples of green infrastructure include tree canopies and rainwater harvesting systems.

Streambank Stabilization

Since many parks are already located along streams, they are particularly well-suited for streambank stabilization projects. In a fully developed community that lacks the open space needed for traditional land-based BMPs, a streambank restoration project in a municipal park offers the greatest opportunity for the community to meet its pollutant reduction goals.

This is the case for New Cumberland Borough in Central Pennsylvania. As part of its 2018 permit application, New Cumberland was required to prepare a Chesapeake Bay Pollutant Reduction Plan. In this plan, the borough had to demonstrate how it will reduce its sediment load as part of a multi-state effort to clean up the bay. The borough proposes to meet a significant part of that goal by planting a riparian forest buffer. This buffer will extend the length of the borough park along the Yellow Breeches Creek toward the creek’s confluence with the Susquehanna River. The buffer will slow down stormwater runoff and even absorb some of it in order to reduce further erosion of the streambank.

A streambank restoration project HRG designed in Cranberry Township’s Graham Park

Incorporating green infrastructure and streambank stabilization projects into municipal park and recreational facilities helps to lower the cost of BMP construction for MS4 compliance, but it has many other benefits, too. In our next article, we’ll discuss more of the benefits of incorporating green infrastructure and streambank stabilization into park and recreational facilities.

Ben Gilberti, P.E., manages civil engineering services provided by Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) throughout Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. He assists with the design of municipal infrastructure like sidewalks, stormwater systems, and sewer facilities.

Ben Gilberti, P.E., manages civil engineering services provided by Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) throughout Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. He assists with the design of municipal infrastructure like sidewalks, stormwater systems, and sewer facilities.

James Feath, R.L.A., is a senior landscape architect at HRG. He has 20 years of experience in the planning and design of public spaces, including parks, trails, and recreational facilities.

James Feath, R.L.A., is a senior landscape architect at HRG. He has 20 years of experience in the planning and design of public spaces, including parks, trails, and recreational facilities.

Park Boulevard Realignment and Fort Hunter Park Enhancements Honored as Premier Projects by Dauphin County

/in Company News, News-Parks & Recreation, News-Transportation, News-Water Resources /by Judy LincolnHerbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) is pleased to announce that two of our projects have been selected by Dauphin County in its annual Premier Projects award program.

Since its inception six years ago, the Dauphin County Premier Projects program has honored more than two dozen projects that promote smart growth and spark revitalization throughout the region. Among this year’s honorees, HRG provided engineering services for two of them: enhancements to Fort Hunter Park and realignment of Park Boulevard.

Park Boulevard

A broad range of local leaders from Derry Township, Dauphin County, and area businesses worked together on the realignment of Park Boulevard to support future economic development in Hershey. The new roadway provides several safety improvements:

- It replaces a 60-year old bridge over Spring Creek, which was structurally deficient and weight-restricted.

- It converts a narrow roadway beneath the Norfolk-Southern underpass from two-way traffic to one-way traffic. This reduces the potential for vehicular accidents and allows for the installation of a sidewalk that is segregated from through traffic.

- It improves emergency response time by adding a roadway connection from northbound Park Boulevard. (Previously, first responders had to drive a circuitous route through several intersections to access this area. Now crews can reach the area 2-3 minutes faster.)

- It provides a new shared-use sidewalk that will enhance safety for pedestrians traveling to Hershey’s attractions from downtown.

- It adds a safe zone for people boarding and exiting buses at the Hershey Intermodal Transportation Center. This zone is physically protected from through-traffic.

Front Row: Chuck Emerick, Matt Weir, John Foley, Susan Cort, Justin Engle

Back Row: Chris Brown, Patrick O’Rourke, John Payne, Brian Emberg, Tom Mehaffie, III, Matt Lena, Lauren Zumbrun

Fort Hunter Park

Fort Hunter Park seamlessly blends new amenities with environmental protection and a celebration of the area’s history and wildlife. The enhanced park includes two new boat launches that provide access to Fishing Creek and the Susquehanna River, new pedestrian paths, new seating to enjoy the scenic views, and new outdoor gathering spaces to accommodate park festivals. It also includes expanded parking to make it easier for locals to access and enjoy these new park features.

To protect the scenic and tranquil environmental setting, engineers used innovative techniques to collect and treat stormwater like porous pavement. They also replaced two paved median areas with soil, stone and native plantings to retain and filter stormwater runoff while enhancing the appearance of the roadway. A new basin for collecting stormwater is designed to blend with the adjoining woodland edge, and herbaceous plantings and indigenous trees help to improve a local habitat area.

Signage in the enhanced habitat area describes local wildlife for park users, while other signs in the park inform visitors of past river activities such as Native American gatherings, early transportation, and coal reclamation.

Chad Gladfelter, Carl Dickson, John Hershey, Matt Bonanno, Steve Deck

ABOUT HRG

Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) is a nationally ranked design firm providing civil engineering, surveying, and environmental services. The firm was founded in Harrisburg in 1962 and has grown to employ more than 200 people in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia. For more information, please visit the website at www.hrg-inc.com.

Premier Projects: Dauphin County Honors Middletown Sewer & Cal Ripken Field

/in Company News, News – Government, News-Land Development, News-Municipal, News-Water & Wastewater /by Judy LincolnHerbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) is pleased to announce that two of our projects have been selected by Dauphin County in its annual Premier Projects award program.

Since its inception five years ago, the Dauphin County Premier Projects program has honored 23 projects that promote smart growth and spark revitalization throughout the region. Among this year’s six honorees, HRG provided engineering services for two of them: the replacement of sanitary sewer facilities in Middletown’s downtown business district and the construction of a state-of-the-art youth baseball field at the Harrisburg Boys and Girls Club.

Middletown Sewer Replacement

| (Left to right) County Commissioners Mike Pries and George Hartwick,III, HRG Staff Professional Staci Hartz, Middletown Public Works Superintendant Ken Klinepeter, and Tri-County Regional Planning Commission Executive Director Tim Reardon |

The replacement of Middletown’s sanitary sewer lines played a crucial role in promoting renewed economic development along South Union Street, which is the heart of the borough’s business district. Some of the sewer mains in this area were close to 100 years old and had deteriorated enough that community and business leaders feared a collapse could endanger streetscape improvements in the area. This project successfully replaced aging infrastructure and eliminated a cross-connection between the borough’s sanitary and stormwater systems that had caused several sewage overflows near Hoffer Park as well as sanitary sewer back-ups in businesses along South Union Street. Without excess water entering the system during wet weather events, the sewer authority has additional capacity available and is able to extend service to nearby growing communities in Londonderry Township and Lower Swatara Township (which, in turn, can promote further economic development in those areas, as well.)

Cal Ripken Senior Youth Development Park

| (Left to right) County Commissioners Mike Pries and George Hartwick,III, HRG Eastern Region Vice President Andrew Kenworthy, Harrisburg Boys and Girls Club Director of Development Blake Lynch, and Tri-County Regional Planning Commission Executive Director Tim Reardon |

The Cal Ripken Senior Youth Development Park at the Harrisburg Boys and Girls Club provides recreation and character development opportunities for disadvantaged youth. The park was funded through the Cal Ripken Senior Foundation, which supports the development of baseball and softball programs in distressed communities. This initial donation inspired other businesses and community organizations to pledge their own financial support for the athletic facility and its programs, which include Little League, a summer soccer program, speed and agility camps, flag football, and lacrosse.

The facility is located in an economically disadvantaged section of the city and is the only active athletic field available for youth in that area. As such, it offers kids a safe space for recreation to keep kids busy and engaged in healthy pursuits.

ABOUT HRG

Originally founded in 1962, Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) has grown to be a nationally ranked Top 500 Design Firm, providing civil engineering, surveying and environmental services to public and private sector clients. The 200-person employee-owned firm currently has office locations in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia. For more information, please visit the website at www.hrg-inc.com.

Van Voorhis Trailhead Project Creates Recreational Resource Out of Former Brownfield

/in Company News, News-Parks & Recreation /by Judy Lincoln HRG is proud to have worked with the Monongahela River Trails Conservancy on converting a remediated brownfield site into a popular trailhead on the Mon River Rail-Trail in Star City, West Virginia. Formerly the site of a glass manufacturing facility, Monongalia County Commission completed remediation of the site in 2012, paving the way for this formerly contaminated property to be converted into a valuable recreational resource for one of the fastest-growing residential areas in the region.

HRG is proud to have worked with the Monongahela River Trails Conservancy on converting a remediated brownfield site into a popular trailhead on the Mon River Rail-Trail in Star City, West Virginia. Formerly the site of a glass manufacturing facility, Monongalia County Commission completed remediation of the site in 2012, paving the way for this formerly contaminated property to be converted into a valuable recreational resource for one of the fastest-growing residential areas in the region.

HRG provided engineering services to the Mon River Trails Conservancy (MRTC) to double the rail-trail parking on the former Quality Glass Company site and install the first “Sweet Smelling Toilet” along the nearly 4-mile long trail. This waterless toilet was originally designed by the U.S. Forest Service, and, when properly sited and vented, eliminates the odor and insect problems typically associated with traditional outhouse facilities.

The Van Voorhis Trailhead project was a collaboration of many community partners, including the Town of Star City, the Monongalia County Commission, the North Central Brownfield Center, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, the West Virginia Department of Highways and the Mon River Trails Conservancy.

It was partially funded by a grant from the Federal Highway Administration’s Recreational Trails Program, as administered by the West Virginia Department of Transportation, Division of Highways.

ABOUT HRG

Originally founded in 1962, HRG has grown to be a nationally ranked Top 500 Design Firm, providing civil engineering, surveying and environmental services to public and private sector clients. The 200-person employee-owned firm currently has office locations in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia.