How to Incorporate Green Infrastructure into Parks in order to Save Money Meeting Regulatory Requirements

This article is the third in a series on incorporating green infrastructure into parks and recreational space in order to more cost-effectively meet environmental regulatory requirements. (Part 1 explained why parks are an ideal location for green infrastructure projects to meet regulatory requirements, and Part 2 explained the benefits of incorporating green infrastructure into parks.)

In this article, we provide advice on how communities can identify areas in their park and recreational spaces that are good candidates for green infrastructure and how to work with other groups to get these projects implemented. This article is an excerpt from an article we published in the April 2018 issue of Borough News magazine entitled “Parks Provide the Ideal Location for Meeting Environmental Regulatory Requirements.”

How can municipalities incorporate green infrastructure into their park facilities?

Start by taking an inventory of your facilities and look for places where green infrastructure could be used.

Pay close attention to your hard surface areas. These are the areas that generate the most runoff, so look for ways to reduce the amount of hard surface area or lessen its impact by directing runoff to pervious areas.

Look at your parking lots: How does stormwater flow across the lot? Are there landscaped areas or medians where you could incorporate bioretention facilities? Are there places where you could plant additional trees? Perhaps you could use permeable pavement in the parking stalls.

Watch this video to see a demonstration of how quickly permeable pavement in these municipal parking stalls absorbs a few buckets of water compared to the non-permeable pavement outside the parking stalls.

Do you have paved trails and walkways in your park system? Consider permeable pavement or a tree canopy that runs alongside the path. Because of their linear nature, bioswales can be planted alongside trails or paved paths, too. The following video shows how a system of bioswales along the bike trail in Indianapolis absorbs water during a rain event.

The Magnificent Bioswales & Stormwater Treatment Along the Indy Cultural Trail from STREETFILMS on Vimeo.

Could your athletic fields be used for a dry extended detention basin?

Do you have open space within existing drainage areas that could be used for constructed wetlands?

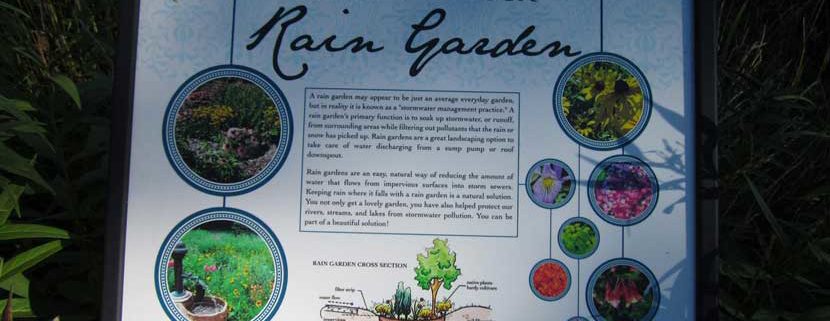

Do you have a community center? This would be a great location for a demonstration rain garden, rainwater harvesting system, or planter boxes. It could even be a candidate for a green roof.

Middletown Borough reduced the volume of stormwater entering their stormwater system by converting the traditional garden located between their municipal building and parking lot to a rain garden. By redirecting the building downspout to the rain garden, the stormwater that previously flowed across the parking lot is now infiltrated on site.

Check out this article in the Middletown Press and Journal about Middletown’s rain garden.

Successfully integrating green infrastructure into your park facilities is a team effort. Municipal administration, public works staff, planners, and the parks and recreation department should all work together to find cost-effective solutions that maximize benefits for the community.

But the teamwork shouldn’t end inside the government offices. Schools, conservation groups, gardening clubs, and other community groups may also want to lend a hand. Bringing them on board marshals additional resources for the cause and helps to build public support for the efforts.

Your municipal engineer can provide valuable guidance on design, regulatory requirements and even potential funding sources.

Municipal staff must be creative stewards of both the environment and the taxpayers’ money. Incorporating green infrastructure and streambank restoration projects into park and recreational facilities helps them do both. By using land the municipality already owns, communities can greatly reduce the cost of construction projects needed to comply with environmental regulation like the MS4 program. The native plantings used in rain gardens and bioswales typically need less maintenance and chemicals than turf grass, and rainwater collected in barrels can be used for irrigation or toilet flushing in order to lower water consumption costs.

At the same time, these projects prevent pollutants in stormwater runoff from reaching our lakes and streams, preserving them for recreational uses like fishing and swimming. They also help to prevent flooding, which ensures the parks department will be able to keep athletic fields and parks open for scheduled activities after a storm.

In these ways, green infrastructure can enhance the recreational experience for the user. It can also enhance the aesthetic appeal: Rain gardens and native vegetation can provide a habitat for wildlife and butterflies for safe public viewing and can serve as a quiet retreat for reflection.

Signage turns these features into an educational experience and helps to meet the educational outreach requirements of a community’s MS4 permit.

Working together as a team, municipal officials, planners, park professionals, and local community groups can protect our resources while providing exceptional recreational experiences for all.

Ben Gilberti, P.E., manages civil engineering services provided by Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) throughout Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. He assists with the design of municipal infrastructure like sidewalks, stormwater systems, and sewer facilities.

Ben Gilberti, P.E., manages civil engineering services provided by Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) throughout Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. He assists with the design of municipal infrastructure like sidewalks, stormwater systems, and sewer facilities.

James Feath, R.L.A., is a senior landscape architect at HRG. He has 20 years of experience in the planning and design of public spaces, including parks, trails, and recreational facilities.

James Feath, R.L.A., is a senior landscape architect at HRG. He has 20 years of experience in the planning and design of public spaces, including parks, trails, and recreational facilities.