This article was originally published in the June 2016 issue of Keystone Water Quality Manager. It is reprinted here with their permission.

We’re all familiar with the phrase “If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will get you there.” This is paraphrased from an exchange between Alice and Cheshire Cat in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Like Alice, you know you need to get “somewhere” because changing regulations, increasing costs, aging infrastructure and customer growth affect the way you provide your service. Each year as operators, managers, and board members, you’re forced to establish budgets, adopt rates and policies, and make recommendations that have long-lasting effects. You may use the best information available at the time but can’t be sure that you’re adequately prepared for what’s just around the corner.

Strategic planning is a tool that helps to identify where you need to go and the best road to get there by exploring the fundamental values and principles that support your utility’s policy and operating decisions. Properly done, it looks at all aspects of the utility’s operations in order to see if they reflect the needs of your customers, ensure regulatory compliance, and generate sufficient financial resources to be sustainable. This is not just a financial plan focused on replacing existing facilities or acquiring new ones, but a comprehensive look at the factors that will drive both short and long-term events and an identification of strategies to address them.

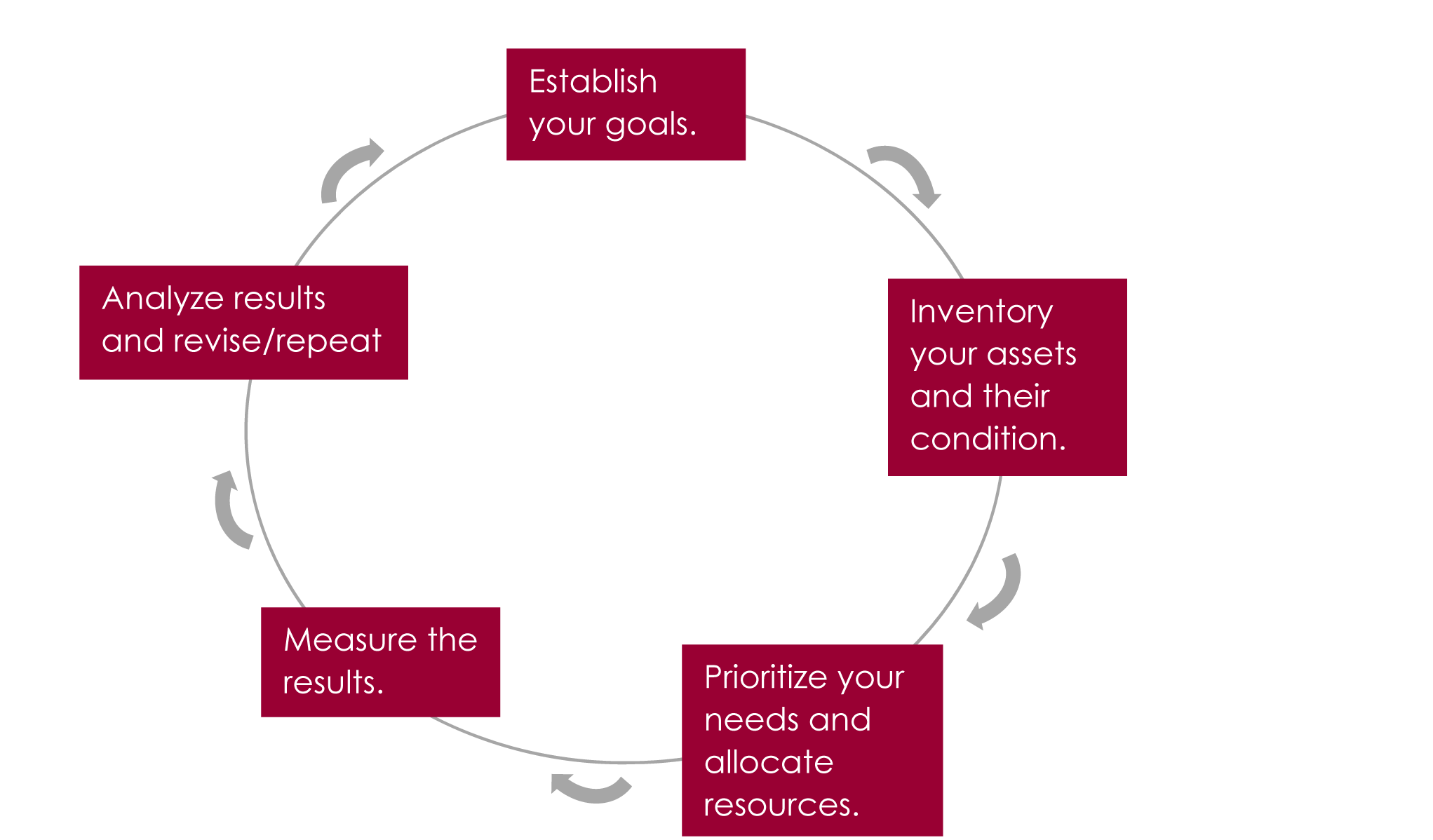

There are five basic elements in a strategic plan:

- Vision

- Mission Statement

- Critical Success Factors

- Strategies and Actions to Meet Objectives

- Prioritization and Implementation Schedule

However, there can be as many additional elements as the utility feels is necessary to properly address the needs of all its stakeholders: its users, employees, and the community at large. Some of these elements may take a long time to complete, while others can be accomplished relatively quickly. For some, a good deal of data will be needed, while others will simply reflect widely accepted industry practices and preferences. The plan could take a month or a year to complete, depending on the level of detail believed to be required. However, one of the benefits of the planning process will be simply identifying the stakeholders and discussing the elements of the plan with them. The ability to identify areas of consensus and concern is a hugely important and valuable outcome of the plan.

Getting Ready for Strategic Planning

Before you can begin the process, there are some preparatory activities that should be completed:

Authorization

The first task in strategic planning is obtaining the authorization to move forward with the process at all. It is important to involve all of the decision-makers in the strategic planning process, and discussing the scope of the plan and its benefits is one of the best ways to achieve “buy-in” for the entire process. Without buy-in, it will be difficult to fully implement the resulting plan.

Identification of Stakeholders

Another important step is to make sure the process considers all relevant points of view. This may seem easy, but, when you actually begin to list them, the number of people and organizations relying on your utility to be well-managed and provide affordable, high quality service is probably greater than you think. While some seem obvious, consider the following examples:

• Current users

• Employees

• Regulatory agencies, including PA DEP and US EPA

• Municipal government, conservation districts and planning agencies

• The Chamber of Commerce or local economic development agency

• Future users, including land owners and developers

This is not intended to be a complete list, only a guide, and not every group will require the same level of involvement in the strategic planning process, but understanding how each group might be impacted is important.

Determination of the Plan’s Time Frame

Determination of the Plan’s Time Frame

Strategic plans are generally long-term, usually five years, but a different time horizon may be more useful if you are aware of some specific event likely to occur just beyond the five-year planning period. If a significant expansion of the utility appears likely, five years may not be long enough.

Organization

How will the strategic plan be organized? Who will guide the process? Is it to be done by an outside professional or internal staff? What is the schedule? What will the final plan look like, and how will it be disseminated? Does it need some type of formal adoption or approval? If so, by whom?

Determining the “Vision”

In essence, visioning asks the question: What will the organization look like in the future? Visioning will supply the context for the other elements of the strategic plan. For a wastewater utility, the visioning process may actually be one of the most involved elements of the plan since this is where you try to get a peek at what’s around the corner. Unlike some businesses where visioning is a projection of some blend of marketing prowess, economic predictions and industry trends, each utility is unique because the factors that drive future events will impact it differently.

The task is made a bit easier if you divide visioning into an external scan and an internal scan. Although they may be related in many ways, the external scan looks at:

- potential changes in the regulatory environment,

- community growth and development,

- changes in demographics,

- future interest rates,

- future construction costs,

- the overall level of economic activity.

(Increased economic activity in nearby communities should also be considered since it may impact your service area.)

The internal scan will focus more on:

- the needs of existing users and employees,

- service improvements,

- transparency,

- facilities,

- finances,

- rates,

- operating policies,

- organizational structure.

These are but a few of the areas that need to be considered in some detail.

The visioning process is almost as diverse as the elements themselves. Clearly, information from outside the utility is necessary. This may include individual interviews with consultants, suppliers and community leaders. Telephone calls, questionnaires, online surveys, and specific messages printed on bill inserts can also solicit feedback from targeted stakeholders. Regardless of how it’s done, the result should be a clear and concise statement that reflects the major trends that are likely to drive the future direction of your utility. But, before you can get too specific, you should develop the broad organizational goals. This is best done with a mission statement.

Drafting Your “Mission Statement”

Drafting Your “Mission Statement”

I know the idea that you can somehow cram the entire essence of an organization into a couple of tightly worded sentences seems impossible. Some mission statements will run on for several paragraphs, but do they really provide more information about the philosophy or principles that govern the utility’s operations? Usually not. Instead, the discipline of packing an organization’s values into a few words may actually provide a better understanding of its goals. Here is an illustration of a short but insightful mission statement for a wastewater utility, courtesy of the Lancaster Area Sewer Authority:

“To provide quality service and apply technology to process wastewater so as to protect and enhance the environment and health and well-being of the community at a reasonable cost.”

The mission statement should not simply be a collection of carefully chosen words that project an image that isn’t consistent with the utility’s values; rather, creating the mission statement should foster a deeper understanding and commitment to those values. This, in turn, provides the benchmarks that measure success.

Identifying “Critical Success Factors”

Identifying “Critical Success Factors”

The visioning process should identify the broad goals and major initiatives that need to be incorporated into the strategic plan. It is not important to determine their feasibility at this point; detailed examination of alternatives will be done later. Simply decide if they are consistent with the mission statement and are not mutually exclusive. Some likely success factors might include:

- Achieving greater transparency.

- Building up operating and capital reserve accounts.

- Having all professional employees become certified in their specialty.

- Exploring alternative billing and payment procedures.

- Creating or reviewing emergency response procedures.

- Reviewing or increasing use of technology to achieve greater efficiency.

- Expanding facilities to accommodate expected population increases.

- Developing an action plan should demographic changes result in reduced flows.

These are only illustrations; the vision and mission statements will help dictate the critical success factors that should be included in your plan. The key here is to keep the success factors general in nature but focused on specific identifiable outcomes. Another important consideration is quantifying what it means to be successful and the metrics for measurement.

From the above illustration, achieving greater transparency is a success factor, but what exactly does that mean? What is it that should be more transparent, and what are the limits of what is made publically available? Can it measured by the number of visits to your website, or does it mean the creation of a website? Is it measured by a fewer number of requests for specific information or telephone inquiries? How about the development of a newsletter? Is that something that most customers believe would be useful based on data collected during the visioning process?

Some critical success factors may not be determined directly. In the example above, data may not have been collected on customer’s preferences during the visioning process. In that case, the success factor of achieving greater transparency will need to be defined by some other precedent activity to measure the benefits of transparency, or it may be determined that transparency is simply a virtue for its own sake whose benefits may not be immediately measurable. In that instance, the precedent activity may be to look at industry practice and see how your current practices can be improved.

If you are getting the idea that developing the critical success factors is a time-consuming process that requires a lot of effort in order to be done correctly, you’re right. This is often the work of several individuals and should involve a team approach at least to direct the work. Care should be taken to assign responsibility for completing an assignment to someone who is involved in the overall planning effort. If not, they may not understand the actual goal and may simply complete a task.

Developing critical success factors, defining them, and providing metrics for measurement is at the very heart of the strategic planning effort. While strategies and actions will provide the “to-do list” and ultimately become the basis for the final report, they will be driven first by the critical success factors you’ve defined.

Developing “Strategies and Actions”

This step is where the plan is actually created. Critical success factors identify the areas where some action seems warranted; they take our broad goals and further define the “somewhere” we want to go. The next step is determining how to get there.

Again, using the transparency example, probably everyone will agree that organizational transparency is desirable, but someone might disagree with the type of information that is made available or with the level of training that may be necessary to organize and screen information. Cost is always a consideration when implementing changes.

Again, using the transparency example, probably everyone will agree that organizational transparency is desirable, but someone might disagree with the type of information that is made available or with the level of training that may be necessary to organize and screen information. Cost is always a consideration when implementing changes.

Because there are generally many facets to each critical success factor, it is important to have several individuals involved in formulating the strategy for evaluation and implementation. This is often accomplished by group meetings, where each critical success factor is discussed. Questions will likely arise that cannot be answered without some further investigation, so tasks must be delegated to a smaller group or an individual for follow-up. In fact, most of the early efforts will be directed to developing the process to obtain the necessary information and assigning someone to gather and analyze it. The analysis is essential so that the success factor can be implemented in a way that achieves its intended purpose. It also provides documentation for any critical success factors that cannot be implemented.

Once the strategy for implementation is determined, specific detailed actions for implementation should be prepared. One of the most important decisions in this stage of the process is timing. You want to think about the best time to launch a new initiative or modify or eliminate an existing one.

Another important task is to identify someone to champion the implementation. Maybe there is one lead person or several depending on the type and number of tasks. If achieving the critical success factor requires technology changes, someone involved with maintaining that technology should be involved in the implementation. This may seem obvious, but sometimes third parties are retained for implementation, resulting in a loss of buy-in from those who will be responsible for making it all work.

Prioritizing Tasks and Designing an Implementation Schedule

Even though this article opened with a reference to a fairy tale, there should be no fantasy about implementation. It’s just as much work as each of the other elements — maybe more, since there are now clear ideas on how each goal is to be achieved and, of course, the devil is always in the details. Regardless of how thorough the analysis was, complications can be expected. Another frustration usually is that it takes longer to accomplish than originally believed.

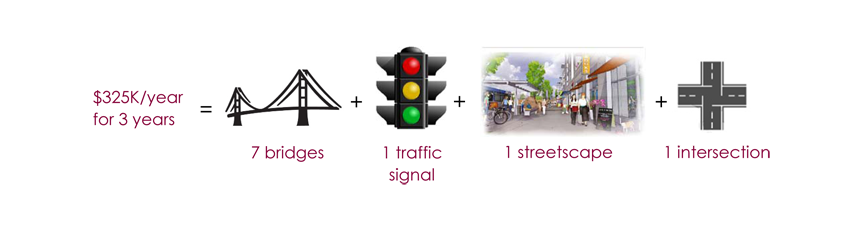

In order to avoid this, one of the first steps to implementation is to determine the schedule. Unless there are very few and straightforward critical success factors, some effort needs to be expended in prioritizing each success factor for each of the broad goals identified in the vision. Often, once the strategic plan is formalized, a sense of urgency to implement its objectives is inevitable. This is understandable since the reason for the plan is generally to improve the utility’s operations, so why would you want to delay?

For one thing, it’s important to remember that the plan itself looks at a five-year time period, so that not all benefits will be immediately available. Also, events are constantly changing, so some of the fundamental assumptions that went into the plan may change. This may not affect the plan, but the implementation schedule should allow time for monitoring external changes nonetheless.

Another important consideration is the time staff has available to implement the plan. While the plan is being implemented, all other work must continue. Even if some of the heavy lifting is assigned to others, the utility’s staff needs to be involved at each step if they are expected to achieve the plan’s goals and provide necessary feedback.

Communicating the Plan with Your Stakeholders

Communicating the Plan with Your Stakeholders

Okay: you have the vision, you’ve determined the critical success factors, you’ve developed strategies for implementation, and you’ve created the implementation schedule. You have assigned staff to implement the various strategies in order to monitor progress and make sure that each strategy achieves its desired goal. One question remains: What does the final plan look like? Is it a printed document, a slide presentation published on your website, or an internal spreadsheet that serves as a checklist for monitoring implementation?

Like all the other aspects of the plan, the process that rolls out the plan is determined by the goals of the strategic plan itself. If the plan is centered on internal improvements, then employee meetings with handouts may be the most effective means of communicating the plan’s objectives and the strategies designed to implement them. If there are elements of the plan that are service-related – that impact your customers or the community at large – more formal printed materials may need to be prepared. Meetings with important relevant stakeholders may also be useful, especially if there are some financial impacts associated with the plan that they are expected to share.

The only thing that’s constant is change. Absent a crystal ball, tarot cards, or an Ouija board, a well-thought-out strategic plan is the best means of seeing the future. Even if it misses the mark, knowing why it missed and what parts of the utility may be affected is an important benefit that makes the exercise worthwhile. At the very least, developing the plan will require policy-makers, managers and staff to consider each other’s points of view and understand how the customers and community view your utility.

Determination of the Plan’s Time Frame

Determination of the Plan’s Time Frame

Drafting Your “Mission Statement”

Drafting Your “Mission Statement” Identifying “Critical Success Factors”

Identifying “Critical Success Factors” Again, using the transparency example, probably everyone will agree that organizational transparency is desirable, but someone might disagree with the type of information that is made available or with the level of training that may be necessary to organize and screen information. Cost is always a consideration when implementing changes.

Again, using the transparency example, probably everyone will agree that organizational transparency is desirable, but someone might disagree with the type of information that is made available or with the level of training that may be necessary to organize and screen information. Cost is always a consideration when implementing changes.

Communicating the Plan with Your Stakeholders

Communicating the Plan with Your Stakeholders

Bruce Hulshizer, P.E., is a project manager in HRG’s

Bruce Hulshizer, P.E., is a project manager in HRG’s